The Anti-Pop Typology

Rafael Luna

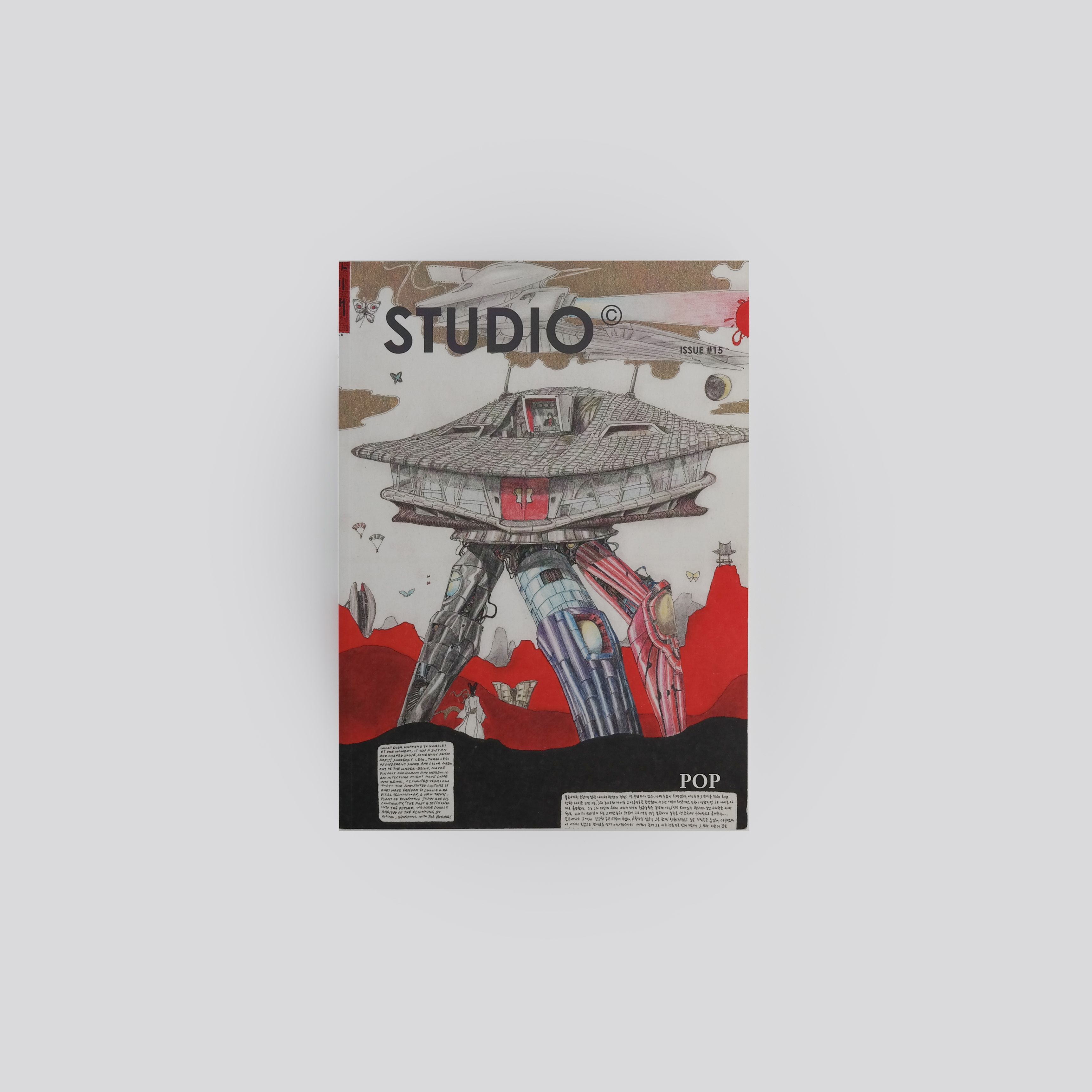

There is no escaping the inevitability of pop-culture in daily life. Through a bombardment of marketing campaigns, pop is assimilated, enjoyed, and revered by the masses. It is a repeatable uniqueness produced by the tools of mass production, yet it is also customizable. Just like Pop-music has been able to produce the majority of its top hits with the same four chord progressions (1,4,5,6), architecture has been able to produce its own pop-chitecture through repetitive strategies. In this essay, pop in architecture will refer to those buildings made to appease the mases, that disguise themselves as a novelty only to reveal the same design progression. Pop has therefore become the repeatable model that constitutes most of our urban fabric. Pop is the new norm, and only through disrobing it, can we produce new works that give order to an ever growing chaotic urban concert through the anti-pop typology. Buildings like the Dongdaemun Design Plaza by Zaha Hadid in Seoul, Taichung Opera House by Toyo Ito in Taiwan, Torre Agbar by Jean Nouvel in Barcelona, stand out not because they are Pop, but because their unique critical language represents a new Anti-pop movement. The post-war era in the United States brough a sense of prosperity in economics and politics that founded the grounds for a consumerist society of conformity that was exemplified with the development of mass-produced suburbia, such as Levittown. As a social criticism of this context, Pop-Art emerged by incorporating the imagery of the everyday items, and consumer goods. The appropriation of the ready-made and mass-produced elements into their art pieces allowed for mass appeal intent, that propagated within the popular culture. Post-war architecture emerged from this same context as pop-art The domino house became a replicable system of development that allowed for the adoption of mass-produced construction a la Ford. Through its rapid development with newer construction techniques, the system because a style, shifting rom Modernism to the International Style. This represented a popularization of the language of architecture into a mass appeal that spread through all scales and disciplines: modern city, modern skyscraper, modern furniture, and modern product design.

Unlike pop-art, which represented a societal critique, modernism became Pop, as in the popular style, and the popular understanding of space, not its critique. Its critique came from the counter projects of post-modernism, deconstructivism, and all the other styles and “ism’s” that have been trying to move beyond the inescapable grasp of pop-architecture, which modernism represents. Pop-architecture in that sense is more relatable to pop music today, which as been able to produce the majority of its top hits with the same four chord progression (1,4,5,6). Modernism became a product of mass appeal, and adoption, comparable to pop-music, its language didn’t change, the same grammar was used to compose variations, much like the top 100 pop hits. The underlying syntax did not come from the production of an original model. This presents a problem in contemporary practice as modernism has become so ingrained in the architecture subconscious that ‘contemporary’ and ‘modern’ have been used interchangeably although they represent different languages. This has sparked the need to rediscover the dialogue in typology within architecture.

The ambiguity between Pop architecture as popular architecture, or Pop architecture as one that pops in the urban context as a means of critique, can only be evaluated by understanding the language of architecture through typology. There is a reason why architecture has become a repetitive exercise of outdoing previous models through the act of novelty in effects, but the lack of typological discussion impedes these buildings to really break away from just doing another Pop tune. To really be novel would require to explore the Anti-Pop typology. First, there must be an understanding of typology in itself, as there is the common misconception of use of typology as a classification of program and use. Building typology cannot be understood as a problem of the program, which Rossi described as a naïve functionalism approach in The Architecture of the City in 1966[1]. Yet over half a century later, program is frequently misused as a synonym to typology in architecture. Buildings can change programs over time, leaving the shell as the only remaining artifact, which can only be dissected through its elements, system, and form. These three categories make up the basis for language in architecture that can differentiate between architects falling under a Pop-trap or emerging as an Anti-Pop.

Elements were introduced in the 18th century by two contemporaries, Abbe Laugier, and Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand. Abbe Laugier discussed the relationship between man and nature and the need for man to protect himself from nature established the basis for any structure or architectural logic that could be composed of basic elements consisting of column, entablature, pediment, floors, windows, and doors. Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand introduced an abstraction of architectural elements through his Precis des lecons d’architecture donnees a l’Ecole royale polytechnique. As explained by Pier Vittorio Aureli[2], while at the Polytechnique, Durand was presented with the challenge of teaching architecture to engineering students by means of a condensed seminar class. In order to do so, he cataloged architectural elements by types, including Laugier’s idea of elements along with floor plans.

This reduced architecture to a taxonomy with the possibility of variation attributed to only the selection of different elements. The idea of elements has been ingrained into the subconscious of academia and practice, only varying by style. A wake-up call was presented during the 2014 Venice Biennale, curated by Rem Koolhaas, under the theme of “Fundamentals,” which shed light at the contemporary practice focusing on a variation of these same elements[3]. It was also no coincidence that in the same Biennale just outside of the main exhibition entitled, “elements”, a reproduction of the Maison Domino was rebuilt as a wood structure[4].

This is no coincidence because the Maison Domino represents the second component, systems in architecture. A system has to do with the way that space is constructed, meaning varying methods of fabrication and construction produced different spaces. As previously explained, the rapid adoption of the Maison Domino diagram as a system for rebuilding a post-war Europe, became a standard of systematic building.

The Domino system presented a singular type of space though, that could only vary with interior partitions or changing the façade. Yet, the language of the domino system remains the same no matter what façade is implemented regardless of the time period. Here lies one of the main problems in the contemporary practice, Pop-architecture is unable to recognize modernism from contemporanism. Practitioners driven by the allure of new methods of fabrication might install a digitally fabricated façade onto a modernist skeleton, in the naïve hope that this façade effect will produce a contemporary building, but it is just slang within the modernist grammar. The system remains modernist, therefore the space remains modernist regardless of the façade intents. To compare to Pop-music, it is Max Martin, Swedish songwriter with the third most pop hits, writing a song for Taylor Swift or Katy Perry, and it makes no different which artist performs it. The music notation might stay the same while changes happen in vocals, lyrics, or instrumentality.

The underlying framework of chord progression does not change, guaranteeing a pop-hit. Although successful in music, in architecture, Pop becomes part of the generic urban fabric[5], part of the “garbage spill urbanism” as described by Patrick Schumacher[6], that can only be ordered by means of the Anti-Pop. The Anti-Pop has been in development since post-modernism, as a series of critiques of the banal sterile environment that modernism produced. As an analogous to Pop-Art and the ready-made assimilation, the New York Museum of Modern Art exhibited “Architectural Fantasies” in 1967, where Hans Hollein presented montages of enlarged familiar objects onto landscapes as a direct critique to modernism. This series of collage projects brough into perspective issues of form in architecture. The formal strategy being the last category for language in architecture. Modernism was more focused on the system than on form, therefore by enlarging an everyday object to the scale of the building, Hollein was immediately producing the sense of a new spatial logic that could not be conceived by the modernist system. This ready-made architecture mimics Pop Arts, yet it remained stronger as a visual art or critique, and not a realized building. If constructed, this formal approach would jump into the arena of Pop, as in kitsch.

As a semiological problem, why would a building need to borrow a symbolic form to be a symbol in itself?

The notorious debate between the “duck and the decorated shed” pinned by Brown, Venturi, and Izenour, a few years later in the 1972 canonical “Learning from Las Vegas” positioned a post-modernity feud in the language of architecture regarding this problem[7]. Form in architecture, should not belong to neither the duck or the decorated. Both represent a kitsch sense of Pop and neither answers to a true dialogue with the urban fabric and spatial context[8]. Architecture does not need to adopt a literal graphical representation of an object to communicate, nor does it need to be a collage of graphical signs to be a symbol or signify. Form in architecture has an intrinsic meaning to space, which was re-examined by Anthony Vidler in 1977 as “The Third Typology[9].” Yet, the modernism and the international style, spread like a virus in the reproduction of space, and not until the turn of the 20th century did form start to break from modernism with a series of Dutch experiments on “Bigness,” as described by Kees Christiaanse. The series of big projects that had sparked in Rotterdam during the 90’s lead to an exploration of massing as a formal strategy between public and private space.

Even though technology has improved in the developments of elements, construction systems, that have allowed formal explorations in relation to public and private space, the construction industry is still in a fordist mode of mass production as a response to an ever increasing urbanity, and the domino diagram still prevails as the popular starting point. Countries like Japan and Korea, which thrive in the Pop culture adoption, are able to replace their building stock every thirty years, allowing for newer buildings to implement new systems of construction that might allow novelty in spatial quality. Korea, for example, has been able to develop enough of an urban fabric to house twenty million people, yet the variation in design in newer buildings is found mainly through their facades, while an inner modernist logic prevails. Zaha Hadid Architects’ Dongdaemun Design Plaza stands out among a sea of highrise buildings filled with commercial signs in a regenerated district of Seoul. Already polemic, even before its conception, this behemoth of a building cover an entire city block where two stadiums once sat.

Its fluid form deflects any traditional sense of elements such as windows, doors, roof, walls, or any clear reading of a columns and slab system that fills all the neighbouring buildings. The exuberant uniqueness of this building is often misunderstood as Pop in the sense of a shocking building in relationto its context, like a pop-star. Instead, is an emblematic Anti-Pop typology that breaks from the popular, or kitsch understanding of architecture and urban space brought by trends, fads and modernism. The merger between elements, system, and form into a singular logic expresses a contemporary language of fluid space.

The notion of contemporanism spreads from this logic of not repeating a Pop (popular) language, instead, creating its own. Buildings like Torre Agbar in Barcelona by Jean Nouvel, Taichung Opera House by Toyo Ito, Seattle Public Library by OMA, are all anti-pop typologies in the same fashion. In their explorations of escaping the traditional modern sense of space, these buildings have become icons in their respective cities. Their recognition has come from their separation and distancing from the generic pop milieu. Pop has a recognizable flashiness that is easy to assimilate due to its repetitive language, and ready-made adaptations. The Anti-Pop explores spatial holistic logic where form gets composed by a merger of elements and systems. Elements become openings, voids, in structural three dimensional patterns that form spatial systems that can be parametrically adapted to their context and programs.

This would relate more to an understanding of typology as a rule base logic that cannot be copied or repeated. These anti-pop typologies are unique, and stand out from the generic not as novelties of affect, but as true transcenders to a new approach in architecture.

Notes

[1] Rossi’s development of urban theories lead to the establishment of Urban artifacts as the fundamentals for the reading of the city. This establish a relationship between architecture form and city form.

[2] During his November 20, 2013 lecture at the AA, Pier Vittorio Aureli explained the standardization of Design under Durand’s Precis.

[3] Rethinking Windows. Part of the Fundamentals exhibition at the Venice Biennale 2014.

[4] Maison Domino built out of wood framed structure by Valentin Bontjes van Beek and students from the Architectural Association in London for the Venice Biennale 2014 for the one-hundred year anniversary of the diagram.

[5] Seoul represents the rapid growth of a city following western models for architecture novelty, only to produce the same generic fabric.

[6] From Patrick Shumacher’s lecture “Parametric Order – 21st Century Architectural Order” at Harvard GSD

[7] Analysis on Las Vegas as the basis for fomenting Postmodern theories.

[8] Handbag building in Sinsa, Seoul, as “Duck Building.” Wrapped façade building in Hongdae as a “Decorated Shed.”

[9] Anthony Vidler’s essay in Oppositions Reader 1998