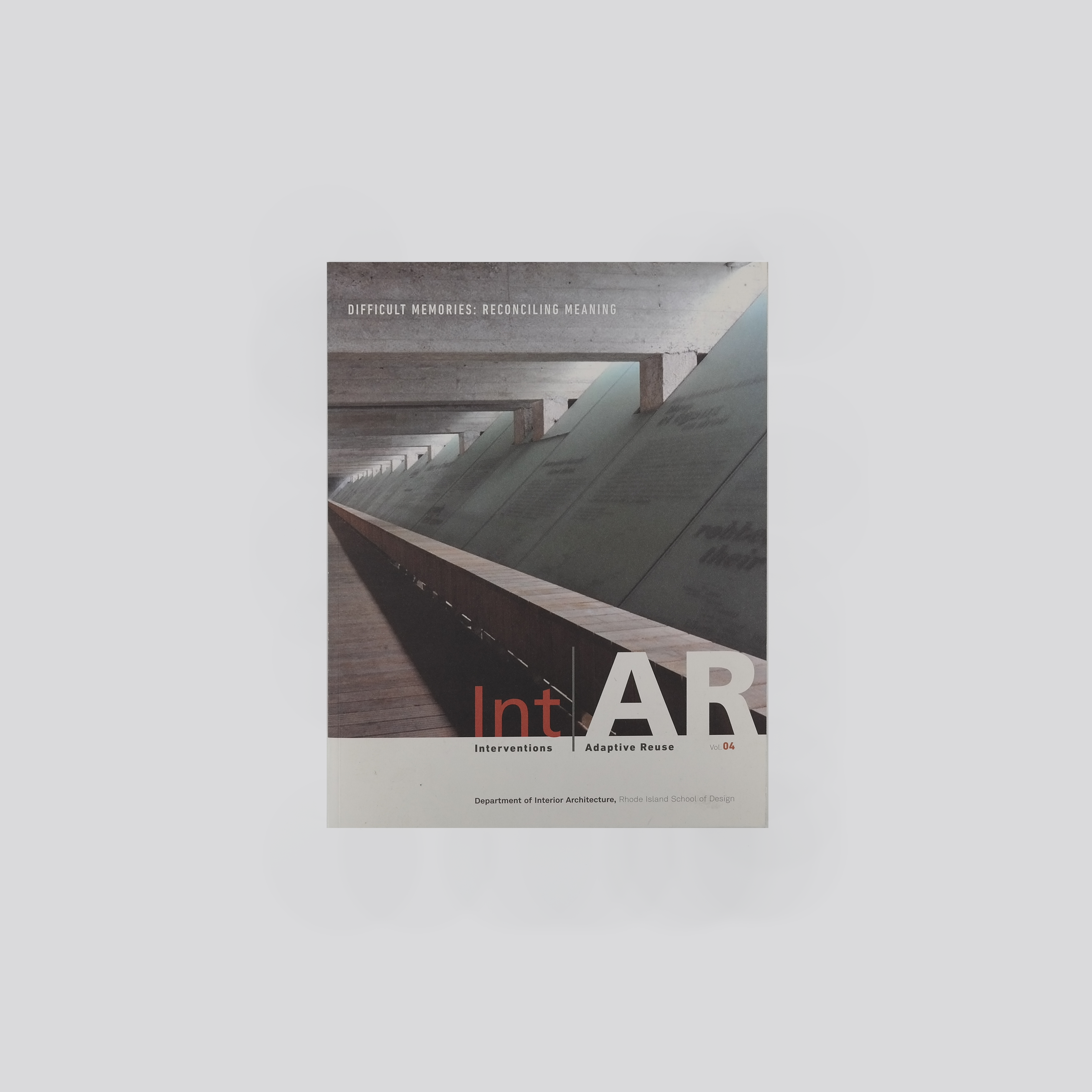

Life of a Shell and the Collective Memory of a City

Rafael Luna

At the end of 2011, the Division of Capital Asset Management of Massachusetts decided to sell one of their properties in Cambridge, MA, and formulated a ‘Request for Proposals’ to which eight developers answered. The intent of the RFP was to redevelop the Edward J Sullivan Middlesex County Jail, one of the most dominant buildings in Cambridge’s skyline, and give a new use to the building.

The RFP received such public notice not only because of the scale of the building, but because of its current use. As a public maximum security building, where civil rights are tried, it poses an irregular exercise for architects and developers to reconcile its difficult memory not only with potential new program, but also with new users. This condition questions the value of the architectural language where the shell and its interior architecture are disassociated, rupturing the inherited difficult memory.

Can this idea of “Difficult Memories” be diluted by an architectural language of autonomous settings that allows interior memories to be ever changing? This is important for contemporary architecture; to value the memory of a building and to allow a future reciprocity between the shell and a changing interior. For adaptive reuse, this dissociation between a building’s interior architecture and its façade or shell, results in three potential relationships; AUTONOMOUS, SYMBIOTIC, or PARASITIC. In cities that reuse their building stock, these three relationships become strategies for retaining, in part, the memory of the building and its past use. Faster cities like Shanghai, or even Tokyo, do not recycle their building stock. Instead, older buildings are demolished for their land value, and entirely new edifices are constructed in building cycles of 30 years using the current technology available. Demolishing and constructing new buildings yield greater freedom for architectural exploration of form, but result in the loss of all cognizance of the collective memory of the city. What then is the role of contemporary architects in creating settings that allow inner transformation, while maintaining the buildings’ memory?

Aldo Rossi was preoccupied with this issue, and criticized the modern movement’s desire to create an abrupt separation from previous models. Peter Eisenman described it as a vision of a sanitized utopia, that superseded the 19th century city or mitigated its destruction after World War II. Rossi saw the city as a theater of human events, each event packed with memories of the past and the potential future. The process by which the city grew became the urban history, and the record of its events became its urban memory. Architecture became an individual artifact within the construct of the collective memory, and replaced its history. Within architecture, history was the link between form and function. As long as an artifact followed its original function to its original form, there was a continuation of historical lineage. As soon as they are separated, history becomes a memory.

In American cities, this idea of the collective memory became more evident following the 1965 demolition of Penn Station in New York City. After this event, the New York Landmark Preservation Commission was formed in order to preserve historically significant buildings and neighborhoods in New York. Other American cities followed by forming their own commissions for preservation and a preoccupation with adaptive reuse ensued to maintain a sense of the collective memory. Historical facades, and structures, remain with their own architectural language, but the original form is disrupted from its original use, initiating the memory of the building. The use of this memory by means of adaptive reuse can be explained further through a closer analysis of three buildings that exemplify the previously mentioned relationships: autonomous, symbiotic, or parasitic. As an American historical city, the City of Boston has had to make use of its building stock, and these three relationships are present in the Custom House (autonomous), Quincy Market (symbiotic), and Liberty Hotel (parasitic).

Autonomy

Peter Eisenman treated autonomy as a process in architecture, a process that escaped modern tendencies by erasing all traces of history and meaning so as to manifest a new self-supporting language. It is also possible to have this autonomy when the shell of the building allows for nonspecific scenarios to occur within it, allowing for an autonomous interior. For adaptive reuse, the process of autonomy is manifested when the interior obliterates all traces of the original function within the building form, ignoring all historical traits of the interior and allowing for the memory of the exterior to exist ONLY as urban fabric. The quintessential example of this condition would be the modern skyscraper whose very nature is to multiply an area vertically. The repeating floor plate becomes an autonomous setting, where the program can change over time. This is characteristic of the first high-rise of the City of Boston, the Custom House. Originally completed at the water’s edge in 1847, it was designed by Ammi Burnham Young in a Neoclassical style. Its form resembled a four-faced Greek temple with an interior rotunda and sky lit dome. The proximity to the docks expedited the inspection, and registration of cargo entering the city. As the shipping industry grew at the turn of the 20th century, the building needed to expand its office space. An additional 16 floors were added on top of the original neoclassical building in the form of a clock tower, completed in 1915 and designed by Peabody and Stearns. At 496ft, it dominated Boston’s skyline, and remained the tallest structure in Boston for almost 50 years. By 1986, the Custom officials moved to the West End, and the building remained unoccupied for 14 years until 1995, when Marriott, the hotel chain, decided to develop the abandoned building as a 87-room Marriott Vacation Club.

The historical transformation that this building has endured embodies the idea of memory as urban fabric with an autonomous interior. If we trace the process of transformation, we can easily unwrap the layers of disassociation between its original form and function to that of today. Its proximity to the docks served a city function, expediting cargo check. When Boston expanded its shoreline through land reclamation, it could no longer facilitate this service and became an office building. As the offices expanded the Custom Officers moved out. Proposals for ruse considered possible transformation of the building into a museum, offices or a residential development. This indicated the necessity to maintain the memory of the building’s shell, while providing a different function inside. The inside was later transformed differently on every floor due to the restrictions of the structural parameters, and the financial need for Marriott to develop as many rooms as possible. This resulted in 22 different floor plans with a variety of rooms.

This is a very common transformation in historical cities, where the memory of the shell holds value for the collective memory of the city. For example, the Georgian Terrace of London forms the majority of London’s city fabric. The repetitious façade serves as a uniform wallpaper throughout the city, while the interiors are modified with different functions.

Symbiosis

Symbiosis is a state of mutual benefit that can occur when one organism attaches itself to another for support. In this case, the empty shell of a building carrying the remaining memories of a building survives by adapting its program. The restoration of Quincy Market in Boston is one such undertaking. Built as an extension of Faneuill Hall in 1826, this 535 ft long granite market hall was originally used to display and sell goods. These usually consisted of meats and produce that were displayed in vendor stalls. The building was designed by Alexander Parris in a Greek revival style with a rotunda in the center of the building. By the 1970’s, the market capacity had reached its limits, and vendors relocated.

The building decayed. In order to maintain the market’s memory, efforts were made to redevelop the building as a different type of marketplace. The stalls for groceries were conceptualized as fast food stalls and restaurants maintaining its original function as a food market.

This model has been repeated in different cities, making the memory of a building more evident. The original function evolves as it adapts not only with a new use but to new users. This shift activates the building’s memory, and creates that symbiotic relationship by keeping present the memory of the building while enhancing it through new use. Unlike the autonomous strategy, which maintains an urban fabric element, this is a place making strategy. It has been repeated in several cities as seen in Baltimore’s Harborplace, New York’s South Street Seaport, London’s Covent Garden, Shanghai’s Xintiadi, among others. The value of the memory of the building is the key element for activating the urban space.

Parasite

In a parasitic relationship only one of the members obtains benefits. When a building is adapted to a new use, unlike autonomy, the new use is feeding off the memory of the building. There is a conscious decision to acknowledge the memory of the building in order to enhance the value of the new interior programming. The spatial quality and architectural language become as valuable as the historic quality, sometimes they are even more important for the new program. The most common example in the post-industrial city is the loft; factories turned into living units in order to offer a new spatial quality and larger area that would otherwise not be obtainable in a dense city. The search for these niche real estate development markets often results in parasitic relationships, as was the case for the Liberty Hotel in Boston, a county jail converted into a luxury hotel intended to dominate the boutique hotel market.

The original building for the Liberty Hotel, the old Suffolk County Jail, was completed in 1851 and designed by one of Boston’s most famous architects of his time, Gridley James Fox Bryant. It served as a prison for almost 120 years until the 1970’s when the prison was closed for unfit conditions. The prisoners were transported to the new county jail by 1991, leaving the building empty, and obsolete. Plans were made to reuse the building, maintaining some of its characteristic architectural elements and space. By 2007, it was converted into the luxury hotel, adapting some of the cells into restaurants, bars, lounges, and the atrium into the main lobby. The parasitic relationship between the memory of the building and the current use is the novelty of merging two typologies: the programmatic elements of one typology with the spatial configuration of the other, in order to create a new spatial quality activated by the memory of the building.

Back in the 1850’s, prisoners rioted against being served lobster too often, lobster being food for servants and prisoners during that period. Today, people pay for the experience of eating lobster in a cell. This dynamic relation between memory and current use is beyond that of a spatial relation. This relationship has been capitalized for the purpose of the hotel, and results in a new typology: “jail-hotel.” Although the resultant typology is not a true programmatic hybrid, it has spatial conditions that could not have otherwise been achieved by the architect alone.

All three relationships between the memory of the shell and the interior re-adaptation have very specific characteristics: autonomous to maintain urban fabric, symbiotic as a strategy for place making, and parasitic to generate a new typology. These are strong starting arguments for new adaptive reuse projects, and one way to approach memory and innovative interior spaces. With this in mind, what could be the future tranformation for the Middlesex County Jail building? The scale of the building alone constitutes a whole city block, and its Brutalist façade has a lack of fenestration indicative of its interior role, which is true to its original function and form. Some of the proposals made by developers suggested stripping the building to its bare structure and encasing the building in glass, erasing all traces of its past memory. This presumes that the memory of the building is worthless or unwanted because of its previous social stigma. In reality, as seen on the previous examples, acknowledging this hard memory yields imaginative and unprecedented typologies where the memory can be reconciled with a new program. If the strategy was one of autonomy, then the value of the architectural language is in question. The potential here is in generating a programmatic parasite that constructs new types. For example, what would it mean to live in a 8’ x 10’ cell that has been transformed into a residential minimum dwelling? Or what potential new ways of living could take advantage of the space in order to create an urban vertical core for the city.

For contemporary architecture, it is important to value the memory of a building to allow a future reciprocity between the shell and a changing interior. Adding to Rossi’s criticism of the modern movement, the “Domino System” of Le Corbusier, allowed for that autonomy to occur at an interior level. The diagram of the system, however, has no façade, and therefore, no inherent system for building memory. It was up to the architect to decide on a façade system. This leads to an architecture lacking historic value for preservation. In a sense, it raises the question of models for constructing building stock in the city, which is why faster growing cities opt to construct new buildings rather than reuse their current stock. The criticism here is to reevaluate the modern domino system as one that lacks the ability to provide a collective memory. We often question what is contemporary because of the resistance to escape the modern method of fabricating space. Although not built, the New Deichmanske Main Library by Toyo Ito, a competition entry that would house library programming as well as dwelling, and office spaces using the same system, is a clear example of a contemporary method of fabricating space where façade and interior come from the same system, allowing for reciprocity between the two. This generates an autonomous setting inside that can be adapted to a variety of programs. Although the competition was not won, a section of it was built as a museum. This versatility proves the autonomy of the system housing a changing program, making it worthy of re-adapting, preserving, and more importantly, building a collective memory.

Adaptive reuse is dependent on contemporary architecture. It operates within a predisposed setting. As such it is critical to recognize that contemporary architecture has the responsibility not only of providing a setting for current use, but also for unprecedented future ones. This autonomy is not to have “sanitized utopias” where difficult memories get diluted, but for the possibility of allowing memories to continue to develop, be it difficult or not. If the city is a theater of events, as Rossi conceptualized, then its architectural elements are the stage where memories are built into a collective unit.